Last week we made a second group trip to Reedy Creek. It was the perfect early autumn day to explore Forest Hill Park. I found this section of the creek much more enchanting than the section we saw last month. Undoubtedly the city feels the need to keep up appearances in the park, and that shapes and skews our experience of nature. The interesting thing about Reedy Creek is how different it feels at each section. Upstream, the creek is contained within a concrete channel, giving it a distinctly utilitarian feel as it serves to drain water into the James River—it’s like a glorified drain pie. Further downstream it feels more wild, and inside Forest Hill Park it becomes a destination for the community.

As we walked along the creek and approached a concrete footbridge, Laura mentioned playing a game of “Pooh Sticks,” referencing A.A. Milne’s Winnie-the-Pooh. Standing on a bridge over flowing water, two people lean over and drop twigs into the water before rushing to the other side of the bridge to see whose stick traveled fastest. I hadn’t heard of the game until my wife Sally Ann introduced me to it on one of my first visits to her hometown. At the center of Aiken, South Carolina is Hitchcock Woods, a park that easily conjures imagery of the Hundred Acre Wood from Milne’s books. We reenacted her memories of reading Winnie-the-Pooh and playing Pooh Sticks in the woods.

Recently I’ve been reading Martin Heidegger’s The Will to Power as Art, and I see a connection to the ideas we’ve been exploring with this project. He writes about the nuanced Greek philosophical ideas of physis and techne. Physis is the natural world, anything that comes into being and fades away all on its own, specifically without human interference. Techne is simplistically understood as the term for craft or art, but more broadly it means human intervention on nature, “that knowledge which supports and conducts every human irruption into the midst of beings … the kind of knowledge that guides and grounds confrontation with and mastery over beings, in which new and other beings are expressly produced and generated in addition to and on the basis of the beings that have already come to be (physis). This push and pull between physis and techne informs broader ideas about the Anthropocene Epoch, and more specifically, my thoughts on the Reedy Creek project.

The Reedy Creek situation is a microcosm of the larger push and pull between human development and the natural world. In my project, I am looking specifically at suburban development and its inherent paradox—we want to live alongside nature, but we alter and destroy it to make that possible. Instead of accommodating nature, we end up remediating it. The result is dislocation and fragmentation.

I am exploring ways to visualize this fragmentation and the tension between physis and techne. My first step was creating a simple illustration of the community around Reedy Creek, incorporating a few iconic pieces of suburban development. The area around the creek is more typical of older suburban development, but a few key markers are there—grids of single family homes with yards, cul-de-sacs, and parking lots along the commercial strips. The creek is represented in its form as a concrete channel and in its most natural form downstream. Referencing the old-school game of sliding numbers, I began playing with the deconstructed forms in physical space. This led me to explore the idea as a screen-based interactive experience. I like the possibilities afforded by the web, but this feels more like a single piece that needs the framework of a larger installation.

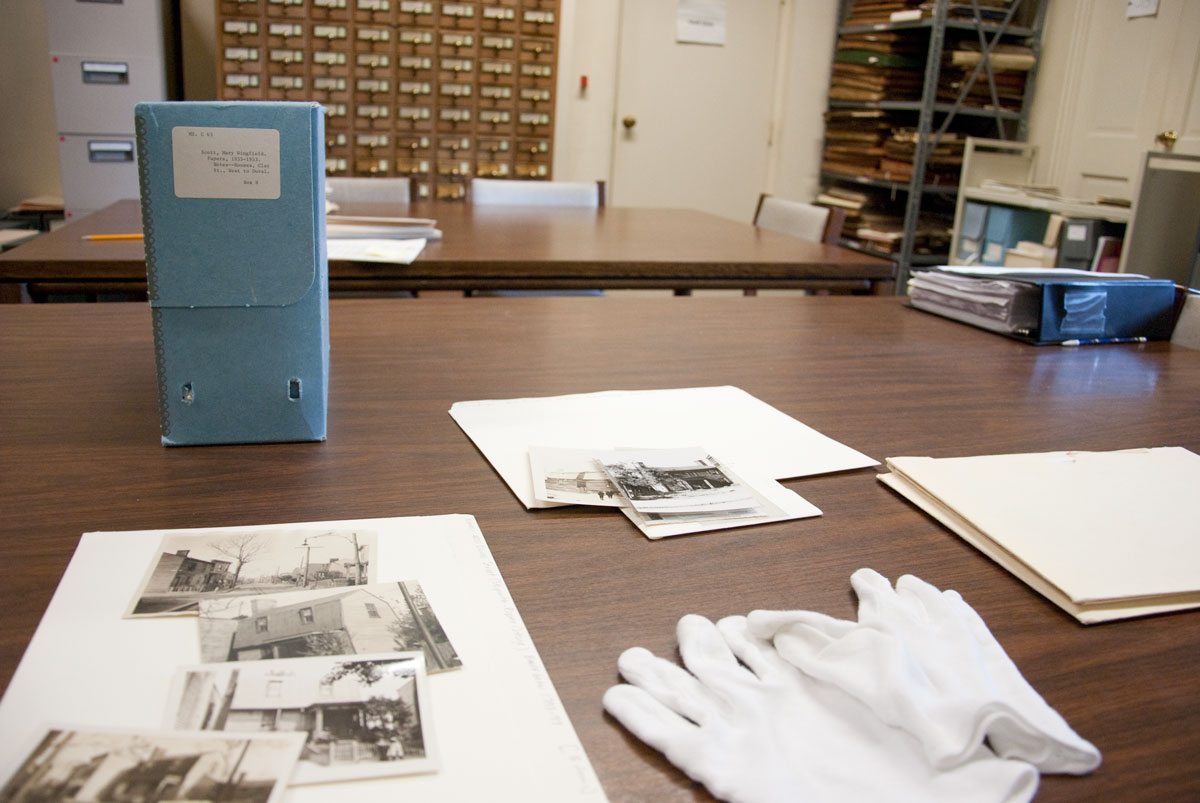

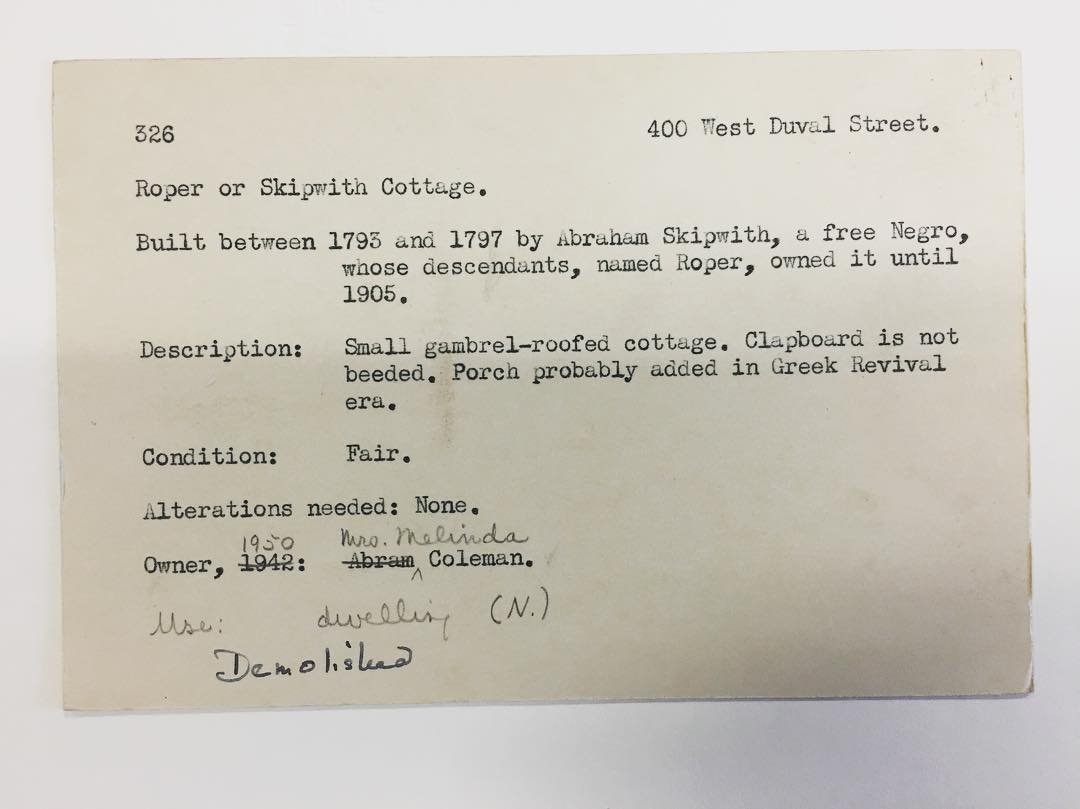

The architectural form of the Skipwith-Roper Cottage and the story attached to it become symbolic of the larger issues in the neighborhood after the disruption of the highway. A simplified gambrel-roofed cottage crafted in clear acrylic holds sleeves with layered imagery, iconography, and text. The piece functions as a condensed visual archive of primary source materials and as a narrative timeline. It is ghostly and clear, with all of its interior contents exposed and out in the open. The clarity of the sleeves changes depending on how they are viewed—from the side, the layered images obscure each other in a dissonant mass of texture, with details coming into focus only on closer look. Moving around to a three-quarter view yields more resolution. The sleeves are also movable, an interactive experience alluding to the act of doing archival research.

The architectural form of the Skipwith-Roper Cottage and the story attached to it become symbolic of the larger issues in the neighborhood after the disruption of the highway. A simplified gambrel-roofed cottage crafted in clear acrylic holds sleeves with layered imagery, iconography, and text. The piece functions as a condensed visual archive of primary source materials and as a narrative timeline. It is ghostly and clear, with all of its interior contents exposed and out in the open. The clarity of the sleeves changes depending on how they are viewed—from the side, the layered images obscure each other in a dissonant mass of texture, with details coming into focus only on closer look. Moving around to a three-quarter view yields more resolution. The sleeves are also movable, an interactive experience alluding to the act of doing archival research.