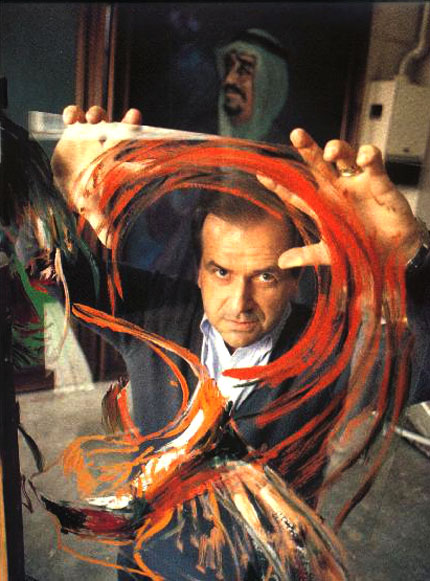

The Modern-Day Court Painter

Andrew Vicari, self-proclaimed “King of Painters. All images are from the BWW Society.

As I discussed in my last post a few days ago, imagery and symbols play an important role in how we remember the past. Going along with that theme and applying it to institutions like governments and organizations, it’s a pretty common occurrence to see the use of imagery as a means to subtly project a level of legitimacy and to tell a preferred story of past events.

An amazing and quirky example comes to mind that I’d like to share: A month ago, I read an interesting article in the New York Times about British artist Andrew Vicari. This man somehow found himself on board a plane destined for oil-spewing Saudi Arabia in the 1970s, where he made a series of connections that landed him the role of court painter to the ruling House of Saud. On the unsteady political ground of the Arabian peninsula, the Saudi royal family looked to Vicari to provide them with large, gradiose paintings that told the story of their rise to power. Over the course of several decades, Vicari wined and dined with royal elite from all over Europe and the Middle East while reeling in obscene amounts of money for, quite frankly, nothing more than cliché-laden amateur work.

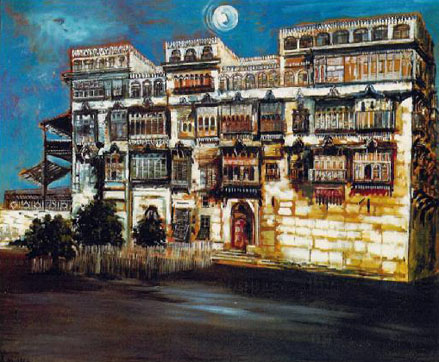

Palais a Djeddah, 1978.

At that particular time and place, the Saudis were more than willing to shell out lots of dough to decorate the walls of their palaces with Western-style art that celebrated their rise to power. The Saudi monarchs see his work as a means of somehow connecting themselves with the cultural and political influence of the West—an aspiration now shared by some members of the Chinese social elite, who have also apparently begun embracing Vicari’s paintings. Meanwhile, on the home front, art critics and collectors haven’t always been so keen on Vicari’s work. Case in point: one painting of his topped out at under $100 at auction in the UK.

The Rape of Kuwait, 1991-1992.

Vicari’s work garners completely different responses depending on what continent he’s in. In the end, the perception of art really does depend heavily on context. In the context of the Saudi court, Vicari’s work finds a captive audience, who themselves, hope to craft their own context for legitimate authority to rule. In the West and especially in the context of the contemporary art scene in London, his work finds no captive audience when compared to the highly conceptual work of oh, say Damien Hirst.

For more on Andrew Vicari, check out these articles about him in the New York Times and The Guardian, and have a look at more of his work here.

You say that the western world cares far less for Vicari’s work than his Saudi and Chinese employers, and you support this by mentioning that one of his paintings sold for less than one hundred thousand dollars in the UK. To me that still seems like a lot for a painting, so what are more respected artists in the Americas and Europe raking in?

I actually said $100, just two zeros. But this brings up a good point that the monetary value attached to art depends on a lot of things. It can almost be compared to how stocks gain and lose value. It also is a matter of the collective taste and Vicari’s work just doesn’t seem to find a place into the art market in the West right now. Who knows, his work could come into vogue and gain value in the UK. There’s a great book by Steve Martin—you know, the famous actor (but actually a really good writer too)—called An Object of Beauty It’s fiction, but it gives a really in depth glimpse into the art world on the gallery/money handling side of things.